How Julia Child Mastered French Cooking and What It Means for Programming

By: Amy M Haddad

Something about Julia Child caught my attention. This American author, teacher, and television personality is famous for bringing French cooking to America. Indeed, mastering the French cuisine and having such a remarkable cooking career is impressive.

Something about Julia Child caught my attention. This American author, teacher, and television personality is famous for bringing French cooking to America. Indeed, mastering the French cuisine and having such a remarkable cooking career is impressive.

But what’s equally impressive is that Child found her “life’s calling”—French cooking—when she enrolled as a student at the Le Cordon Bleu school of cooking at age 37. In other words, Child wasn’t a French cooking child prodigy. Rather, she learned the art and craft of French cooking later in life. Inspired and curious, I picked up her autobiography, My Life in France.

At the heart of my pursuit was this question: how did Child learn French cooking and eventually become a master of it, given her later start?

The answers, I hoped, would help me in my own pursuit for becoming a better programmer. So what follows are three tactics Child used to learn French cooking and how we can apply them to our craft as programmers.

1. Do it the right way.

In 1949 Child enrolled in the Le Cordon Bleu in France, where she was living with her husband, Paul. There, she received instruction from Chef Bungard, who was a sticker for doing things “the right way.”

Instead of memorizing recipes, Child found herself learning the art of French cooking. “Bugnard set out to teach us the fundamentals,” Child explains. “[He] drilled us in his careful standards of doing everything the ‘right way’. He broke down the steps of a recipe and made them simple. And he did so with a quiet authority, insisting that we thoroughly analyze texture and flavor.”

Furthermore, Chef Bugnard emphasized the importance of “proper technique”, Child recalls, “such as how to ‘turn’ a mushroom correctly.”

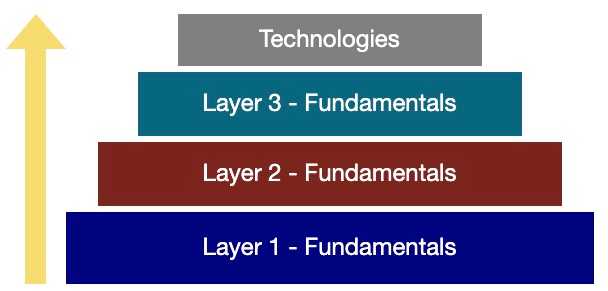

This lesson—focus on the fundamentals—is timely. Instead of the “top-down” approach toward programming by learning the latest technology, we ought to follow Child’s lead and take the bottom-up approach: focus on the fundamentals of programming, like data structures, algorithms, and computer memory.

This fundamentals theme is seen in Child’s cooking career after Le Cordon Bleu. For example, when she and several friends started a cooking school, they “focused on French food...and classical technique, as we felt that once a student has the basic tools they can be adapted to Russian, German, Chinese or any other cuisine.”

Child hits on a critical point about why the fundamentals matter: you’ll be more prepared and adaptable. Once you’ve got the tools of your trade, you can apply and re-apply them in different contexts. And in a fast-changing field like programming, being able to adapt quickly is a necessary skill to have.

2. Do quality work.

As Child rightfully points out: “[g]ood results require that one take time and care.” She adds that “[I]f one doesn't use the freshest ingredients or read the whole recipe before starting, and if one rushes through the cooking, the result will be an inferior taste and texture.”

Simply put: do quality work, which means slowing down, paying attention to details, and setting a standard for yourself. It’s always so obvious when someone “takes time and care” in their work.

All of us have experienced a salesperson who made a shopping experience stress-free, even pleasant. Or the owner of a company included a personalized, hand-written note in your recent shipment thanking you for your order. Or an author included a few extra steps in a “how-to” article to clearly distill the process for the reader. These small gestures take a bit of time. They also show that they care.

Similarly, you may have read a program and found the process effortless: variable names were clear and meaningful; each function served a specific purpose; useless lines of code were removed; lines of “dead code” were removed. That’s “time and care” applied to programming.

The benefit is two-fold: It’s better for the person on the receiving end (and oftentimes that person is our future self). It’s also personally more satisfying to produce quality work than something that’s mediocre.

There are several simple ways to produce higher-quality code:

- Use a checklist. It’s quality assurance that your work is complete and accurate.

- Write meaningful variable names. Steve McConnell’s book, Code Complete, offers this excellent naming advice: “State in words what the variable represents. Often that statement itself is the best variable name.”

- Understand the problem first, before typing code. This may seem obvious, but I’m amazed how few people actually take the time to think before they type.

- Refactor. Make your code a bit cleaner, easier to understand, and more meaningful. Not because you have to. But because you’re capable of doing better.

3. Learn from your mistakes.

“Of course, I made many boo-boos,” Child reflects. “At first this broke my heart, but then I came to understand that learning how to fix one's mistakes, or live with them, was an important part of becoming a cook. I was beginning to feel la cuisine bourgeoise in my hands, my stomach, my soul.”

This quote underscores the key reason why learning from your mistakes—and figuring out how to fix them—matters: doing so will help build your intuition. Child doesn’t use the word “intuition”, but her description of feeling “la cuisine bourgeoise in my hands, my stomach, my soul” certainly suggests it.

Being aware of your mistakes is a key part of the process. There are a few ways to go about it.

First, solve a problem, study the code of others who’ve solved the same problem, and compare the solutions. This is a fantastic way to add tools to your programming toolbox, improve problem-solving skills, and see new (and oftentimes) better ways of doing things. Second, ask for feedback on the problems you solve or programs you write.

Both approaches offer something important: awareness. I distinctly recall when a programmer told me that I should write better variable names. Up until that point I had no idea that my variable names needed help. Feedback brought awareness to the issue at hand.

Awareness is only half of the battle, however. The other is doing something with it. If you ask for feedback on a problem, then apply it. Update your program with the feedback you received or identify a way to sharpen a particular skill.

As soon as I learned about my poor variable names, I created a variable-name checklist and hung it on the wall by my computer monitor. It’s hard to forget about something when it’s in your line of vision.

It’s equally important to learn to spot your own mistakes. The idea is that you train your mind and eye to find mistakes; then fix them.

I use “mistakes” loosely in this particular context. Your code may work, but maybe it could be more efficient or it could be written more clearly. Much of writing is in the editing. Similarly, much of coding is in the refactoring: spot ways to write better and cleaner code.

This is yet another reason why a checklist is useful. Before you consider a program “done,” for example, run through your checklist to ensure your work is accurate and complete.

Make It Active

I can summarize Child’s learning process in one word: active. She did the thing she wanted to get better at: cook.

And cook she did. Not just as a beginner, but throughout her career.

She experimented with recipes and ingredients. She sought the feedback and input of others and applied it. She researched. She constantly asked “why” in order to get to the heart of the matter. “I wanted to know why things happened on the stove, and when, and what I could do to shape the outcome.”

The results speak for themselves: Child is a culinary icon. But for me what really stands out is how she did it. “No one is born a great cook,” she explains, “one learns by doing.”

These are good words to remember the next time you find yourself on cruise control through a series of programming tutorials. Like Child, we must do the thing that we want to get better at. As programmers, we need to program.

← back to all posts